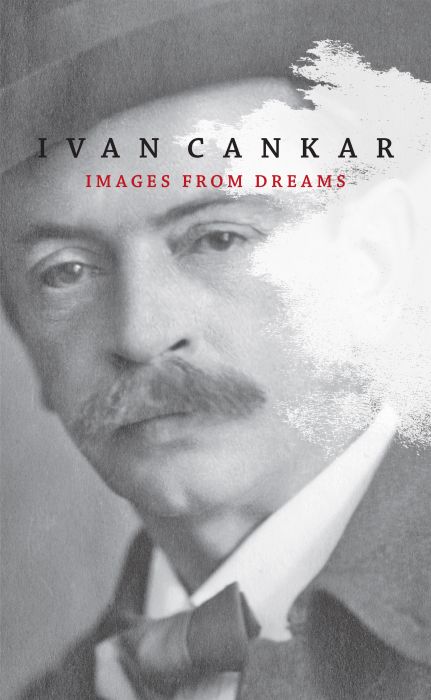

Ivan Cankar : Images From Dreams

Podrobnosti knjige

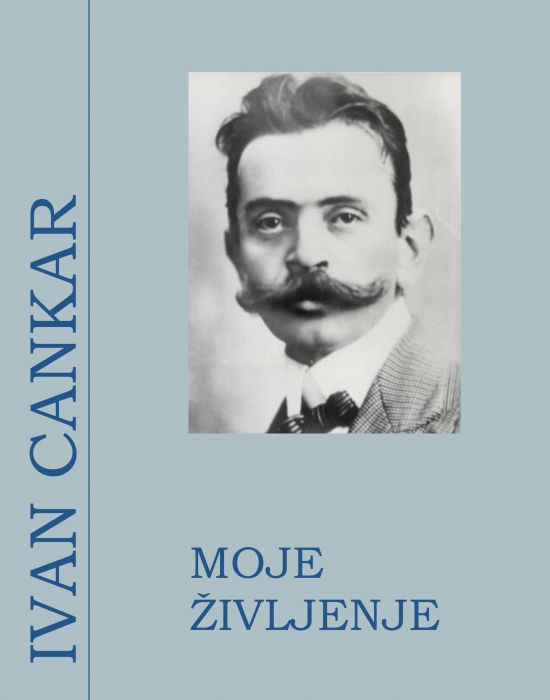

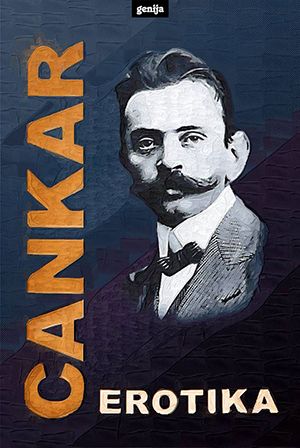

Ivan Cankar is considered one of four representatives of Slovenian modernism (in addition to Murn, Kette, and Župančič). During his years in Vienna, Cankar belonged to a literary circle of Slovenian students of which Oton Župančič, Fran Govekar, and Fran Eller were also members. In 1899, which is now considered the beginning of Slovenian modernism, Župančič’s debut collection of poetry “Čaša opojnosti” (The Goblet of Inebriation) and Cankar’s “Erotika” (Eroticism) were published. The Ljubljana Bishop Anton Bonaventura Jeglič purchased the entire print run of Erotica and destroyed it because of what he described as “the filthy content.” Cankar soon abandoned poetry and began to write fiction and plays. His sketches, stories, novellas, and, later, novels and plays were influenced by the Romantics, naturalism, decadence, symbolism, and impressionism, and also by expressionism. In 1899, Cankar published his first collection of narrative prose. Titled “Vinjete” (Vignettes), the work is distinguished by its personal and lyrical style, as well as its symbolism. Cankar was less influenced by Western modernism and more by the great Russian realists, such as Nikolai Gogol, Leo Tolstoy, and above all Fyodor Dostoevsky, who was conceptually closer to him than Émile Zola and Maxim Gorky and their cold pseudo-scientificism. He also studied Ibsen’s and Shakespeare’s plays, and translated “Hamlet” (1899) and “Romeo and Juliet” (1904). Indeed, his first play, the social-family tragedy “Jakob Ruda” (1900), was written at the same time. Soon after his second return from Vienna, Cankar began to write his first satirical novel. Based on the lives of artists and entitled Tujci (Strangers), it was published in 1901 for the Slovene Society (Slovenska matica). With this work, Cankar launched his war against philistinism and the lack of principle in art and life, a battle that would continue to occupy him until his death. Soon afterwards, he composed a series of short stories that would later be collected in “Knjiga za lahkomiselne ljudi” (A Book for Thoughtless People, 1901) During the same year, Cankar also wrote the satirical comedy “Za narodov blagor” (“For the Wealth of the Nation”), about which he later commented: “I kicked around all the Slovenian progressive, liberal, and patriotic enthusiasm, and the deep love of a simple people.” Even before this work was published, Cankar had clashed with the main advocates of freethinking in Slovenian literary circles of the era, particularly with the naturalist playwright Fran Govekar and the realist Anton Aškerc, from whom he had already differentiated himself in aesthetic and social terms. Cankar developed the type of artistic and political satire we see first in the novel Strangers and in the play For the “Wealth of the Nation”, as well as in many other social satires – in such stories and novellas as “Življenje in smrt Petra Novljana” (“The Life and Death of Peter Novljan”, 1903), “Gospa Judit” (“Madame Judith”, 1904), “V mesečini” (“In the Moonlight”, 1905), “Hlapec Jernej in njegova pravica0” (translated as “The Bailiff Yerney and His Rights”, 1907), “Aleš iz Razora” (Aleš from the Furrow, 1907), the novel “Martin Kačur” (1905), the essay “Bela krizantema” (“The White Chrysanthemum”, 1910), the plays “Kralj na Betajnovi” (“The King of Betajnova”, 1902), “Pohujšanje v dolini šentflorjanski” (“Scandal in St. Florian Valley”, 1908), and “The Serfs” (1910). In these works, he exposes the hypocrisy and mendacity of “bourgeois morals” that are mostly concerned with appearance and that are symbolized by the St. Florian Valley. The individual in conflict with the values of the village, the worker, and the petit bourgeoisie are the dominant themes in Cankar’s work, though his oeuvre also contains other socially critical ideas. He contrasted the St. Florian society of “decent” people with loving and longing, wandering and dying vagabonds, similar to the way Dostoevsky had praised sinners and prostitutes who unhappily strived towards the beautiful and the good. Cankar’s protagonists are often caricatures and exaggeratedly obscurantist, which is why many perceived him as a cultural pessimist and nihilist. Cankar defended himself against this charge in his book of essays “The White Chrysanthemum”: “I show [man] how small he is, how despondent, how he wanders without will or goals; I show him the glory of having no principle, the cult of hypocrisy, the honour of lies, so that he will wake up and recognize who and where he is, and will see into the future […]. I paint the night, desolate and grey, full of shame and sorrow, so his eye will more forcefully strain towards the pure light. My word is thus, however hard and heavy, full of hope and faith! From the night and bog, my devout regard opens towards the heavenly distance!” Between the comedy “For the Wealth of the Nation” (1901) and the book-length polemic “Krpanova kobila” (“Krpan’s Mare”, 1907), Cankar wrote two novels: “On the Hill” (1902) and “Križ na gori” (“The Cross on the Mountain”, 1904). On the path of life, it was the image of his deceased mother that remained his guide – that is, the portrayal of a suffering woman and her living faith, eternal hope, and boundless love. In his novel “On the Hill”, Cankar created a new type of female – or, rather, maternal – novel in Slovenian literature. Cankar’s art achieved its peak during World War I, when he was imprisoned in the Ljubljana Castle as an enemy of the state (before being sent to Judenberg for the aforementioned military service from which he was soon released). During “the years of horror 1914–1917,” a period during which any loose and open word could mean death, Cankar penned “Images from Dreams”, the last book to be published in his lifetime. In this collection of sketches, a work of veiled images that arises from vague dreams expressing his nation’s pain and anger against tyranny, Cankar reached deep inside in order to settle accounts with himself and the world. Images from Dreams is the most poetic of Cankar’s prose works. Janko Kos wrote the following in his preface to Beletrina’s 2018 reprint of Cankar’s work, which had the title “Poslednja Cankarjeva postaja: Podobe iz sanj” (“Cankar’s Last Station: Images from Dreams”): “After 1910, after [his] return from Sarajevo and to the Church, and his parting from Štefka Löffler, his fiancée of many years, and then with his definitive move from Vienna to Rožnik, Cankar’s situation in life changed radically, and at the same time his attitudes towards himself and those close to him, towards his surroundings and historical era, and also towards his own literary work also changed. At this point, he began to open himself to the most profound questions about the meaning of his life up until that point, and about the meaning of the literature that had emerged from that life and world. And what was most important, he began, with this shift, to be increasingly overwhelmed by feelings of moral uncertainty, anxiety, and guilt, and, in his last years, these were combined with thoughts of death and transformed into a desire for a moral ‘cleansing’ or catharsis, for reconciliation with life itself. When World War I erupted in 1914, these personal anxieties were pulled into the much wider and more fateful anxieties of the Slovenian ethnic community and European man. In “Images from Dreams”, personal anxiety and the anxiety of the time converged to the point that Cankar’s experience of the Great War constantly triggered reflections on the most fundamental questions about his own fate and that of the Slovenian ethnic community.” (Kos 197–198)

| Lastnost | Vrednost |

|---|---|

| Založba | Društvo slovenskih pisateljev |

| Zbirka | Litterae Slovenicae |

| Prevod | Jasmin B. Frelih, Erica Johnson Debeljak |

| Spremna beseda | Katja Perat, Robert Simonišek |

| Leto izdaje | 2018 |

| Strani | 315 |

| Jezik | angleški |

| Tip datoteke | epub |

| ISBN | 9789616995511 |

Izvodov na voljo:

- Prost

- Prost

- Prost

-

Zaseden

Še 3 dni 35 min in 6 sekund

Dolg opis

Povezane knjige

Druge knjige avtorja